The Carnegie UK Trust is forefront of research into kindness and how it strengthens community. It is worth spending a couple of hours reading their research reports from the last two years that are themed around kindness.

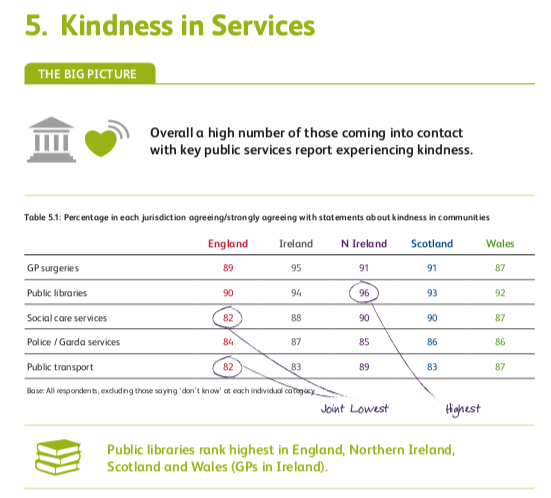

Their output has developed from not even knowing what to call this “everyday help” phenomena , through quantitive studies about where people in the UK find kindness (**spoiler – public libraries came out top**), to asking some hairy questions about how transparency and good governance in public policy may work against kindness.

It is this last idea, of kindness vs. transparency and fairness, that fascinates me as I read yet another news report about a political grub who arbitrarily used his ministerial position to not follow due process, enriching a particular set of people.

From my reading in the last year, I have drawn a few conclusions about kindness. Kindness must be voluntary and discretionary. It involves an act of help of some sort. There needs to be a beneficiary and (my contention is) when the benefactor performs the act, they must aim for a positive outcome and more benefit to the beneficiary than to themselves.

At the core, though, along with all those features there needs to be a simple test, which is “is this a good thing?” If it is not good, then it is not kindness, it is something else. The test may be simple, but actually knowing what “good” is, and how one tells if this act is good, working out “good for whom?” seems ridiculously complex to the point of impossibility.

Now, if we look at the case of Barnaby Grub and the Lucrative Concessions, many of these elements are there. Yes, he voluntarily used his discretion to benefit a set of beneficiaries. It is possible that with political motivation and back scratching involved, there was ultimately greater benefit to Minister Grub than to the individuals helped….but it quacks a lot like the kindness duck.

Researchers have used the term “service nepotism” to describe how some ethnic groups in a market (in this case a group less well-off than others) favour people socially similar to them, challenging ideas of egalitarianism and competition in the marketplace.

In the latest Carnegie publication on kindness, which was released along with the movie embedded below, they discuss the idea of “radical kindness”. Within organisations, there may be people who choose to bend or break rules in order to do good, increase social cohesion and help others. It’s key to remember that kindness is something done by individuals, unobliged. Radical kindness comes in when there is systematic acknowledgement across the organisation that some people’s needs are greater due to structural disadvantage… and there is a social environment and norms where unobligated acts of doing good by individuals are more frequent, to try to level out this inequity. This goes a little way to guiding my “is this a good thing?” test.

The idea is still nascent, but I think all of the examples described above rely on there being a background social environment of unfairness. Of inequity. Of some having more than others. With “radical kindness”, the outcome of the act would be fairer redistribution. With political trough-feeding, inequity would increase.

This links kindness very much to power. Anyone who has opportunity to be kind will have more power in that situation than the potential beneficiary. A key element of kindness, discretion, means there always needs to be a choice by the benefactor to act or not act.

Does this mean that the largest acts of kindness will be found in the most unequal societies? That actually we should aim for a world with less opportunity for kindness? While kindness will always be a good thing (or else it is not kindness, it is something else), possibly finding “more kindness” also says something about the background power relations as well as the level of social cohesion??

I don’t have answers, but I am loving the journey.

Here’s the movie that goes with the latest Carnegie report, outlining ideas arising from the last year of the Kindness Innovation Network across Scotland. Kindness at the University of Glasgow library is mentioned at 1:46.